Are you aspirational? And if you’re a fiction writer, are your characters aspirational?

My paternal grandfather loved to sing. He claimed to have passed himself off as a B-list Frank Sinatra in the recently liberated Parisian bars of World War II. He bragged that the French were so impressed with his singing voice that they painted a full-sized likeness of him on the wall of a famous club, the name of which he couldn’t recall.

In 2000, after providing hazy directions, Pop Pop encouraged me to look for his mural when I first went to Paris as a young man.

I didn’t find it.

I’m pretty sure the mural story was a white lie told to psychologically camouflage the true horrors of my Pop Pop’s WWII experience, but at his retirement home in Lancaster, PA, he really did put on musical shows for his fellow residents. He teamed up with a piano player living right down the hall, selected old-time songs—Makin’ Whoopee and Side by Side were two of his signature tunes—that would get everyone feeling nostalgic, and he wrote original material with my grandmother to get the crowd chuckling and reminiscing in between numbers. He’d record these events, making audio tapes and occasionally even filming. The performances mostly occurred throughout his eighties and later inspired the writing of my novel, Sorta Like A Rock Star.

Whenever I visited him, he popped one of his “programs” into the tape deck or VCR. To be honest, he wasn’t exactly a pro. He often forgot the words. His voice cracked. He coughed a lot. And my grandmother routinely got more laughs than he did. But the audience seemed happy enough to be there and my grandfather lit up with so much pride—both on the screen and sitting there beside me—that I could do little but smile and sing along too.

I think I intuitively appreciated the wabi-sabi-ness, even though I didn’t know what wabi-sabi was back then. His shows were miles from perfect, but still somehow beautiful. An old man clinging to hope.

I’m hearing that famous Dylan Thomas Fern Hill line now:

“Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.”

Last fall, I was regularly zooming with a famous movie director. We were circling a project, trying to figure out a way to adapt one of my novels. A lot was said and the collaboration ultimately (and sadly) did not happen. (Schedules didn’t align.) But the highlight I took away was this: to tell a gripping story, your character has to intensely want something. And in order for an audience to stay invested for two hours, from minute one, they have to be rooting hard for your main character to acquire whatever is desired. This director believed the best way to accomplish the above was to make the character’s aspirations clear and admirable from the very first scene. Perhaps more importantly, the character’s need has to feel immediately existential—on some level, that character’s survival must depend on getting that need met.

When my editor, Jofie Ferrari-Adler, and I worked on We Are The Light, we often used the term ‘life-affirming,’ meaning that life has value, or being positive and optimistic. The book is about tough subjects, but we wanted it to be a celebration of human life, and we think it is.

A life-affirming attitude is also a key part of my mental health / sobriety strategy these days.

For some, the word ‘aspirational’ might be saddled with negative baggage. Maybe it sounds like ‘careerist.’ But ‘aspiration’ is traditionally defined as the hope of achieving something or the process of drawing breath. While the latter definition might seem more essential than the former, most of us need a reason to keep breathing. I think that’s just the way human beings are wired. The characters in our stories are much the same.

When my grandfather reached his early nineties, the retirement home hired professionals to run the music program. My grandfather had been the self-proclaimed star of the Christmas show for a few years, but the new people wanted to take it in a different direction. Apparently—and full disclosure, this is all secondhand info from more than a decade ago—there were whispers that the directors didn’t think my grandfather could sing very well and that he was too old. So Pop Pop was relegated.

For my entire life, when I called my grandfather each and every Sunday night, his greeting would be a cheerful combination of singing and yelling. “HELL-O! MATTHEW!” he’d roar. It was as dependable as the rising and setting of the sun. But that winter, my grandfather’s voice was reduced to little more than a whisper. There was no music in him anymore.

The last few months of his life, I called more frequently.

“You beat the Nazis. You survived World War II,” I’d say. “Surely you can beat this.”

“That was a long time ago,” he’d reply. “I’m an old man. My lungs hurt. I’m too tired.”

“You have more in you! I know it!”

“I don’t think so.”

After the old man passed, my grandmother told me—many times—that Pop Pop died of a broken heart. “Once he lost the Christmas solo,” she said, “it was over. He was never the same.”

Without that spotlight, Pop Pop could no longer summon the will to draw breath. He was no longer aspirational.

I’ve had more than a decade to ponder my grandfather’s demise. He was a larger-than-life character, perhaps the biggest I knew. He was quite frequently full of shit, but he was also charming and optimistic, at least with his eldest grandson. I loved him for it. Fiercely so. Part of me became angry with him for giving up, for psychologically quitting, especially because he left my grandmother behind. He had also promised to see Silver Linings Playbook in the theater with me. But he exited the planet a half year too soon.

After the movie came out, I received an email from one of the nurses who treated my grandfather for many years. The woman said Pop Pop bragged relentlessly about me—saying he just couldn’t wait to see his grandson’s name on the silver screen. Just like he couldn’t wait to share his musical programs with his neighbors and family members.

A year or two before his death, my grandfather called and asked if I would help him do some professional recording. His church needed some expensive repairs. He thought he could save the day by selling CDs of his singing. It was a tough conversation, walking him through the realities of putting out your own music. He didn’t have the necessary start-up funds and, at the time, I didn’t have the financial means to help him. I also didn’t have the heart to tell him how many CDs he’d have to sell to recoup the recording and production costs, let alone raise thousands of dollars for his church, especially in the era of digital music. I knew the market for his singing was not as big as he imagined, and I resented him a little for putting me in the difficult truth-telling position.

But after a decade of missing him, I’d do pretty much anything to sit in his tiny mothball-smelling living room with the heat turned up too high, both of us watching one of his ‘programs’ as he sings along from the cushiony comfort of his recliner.

I wish I had a CD of his singing voice.

I’ve heard other writers say it doesn’t matter if your protagonist succeeds, it only matters if your protagonist tries. And my grandfather spent most of his life trying. He tried for ninety-one years and three months.

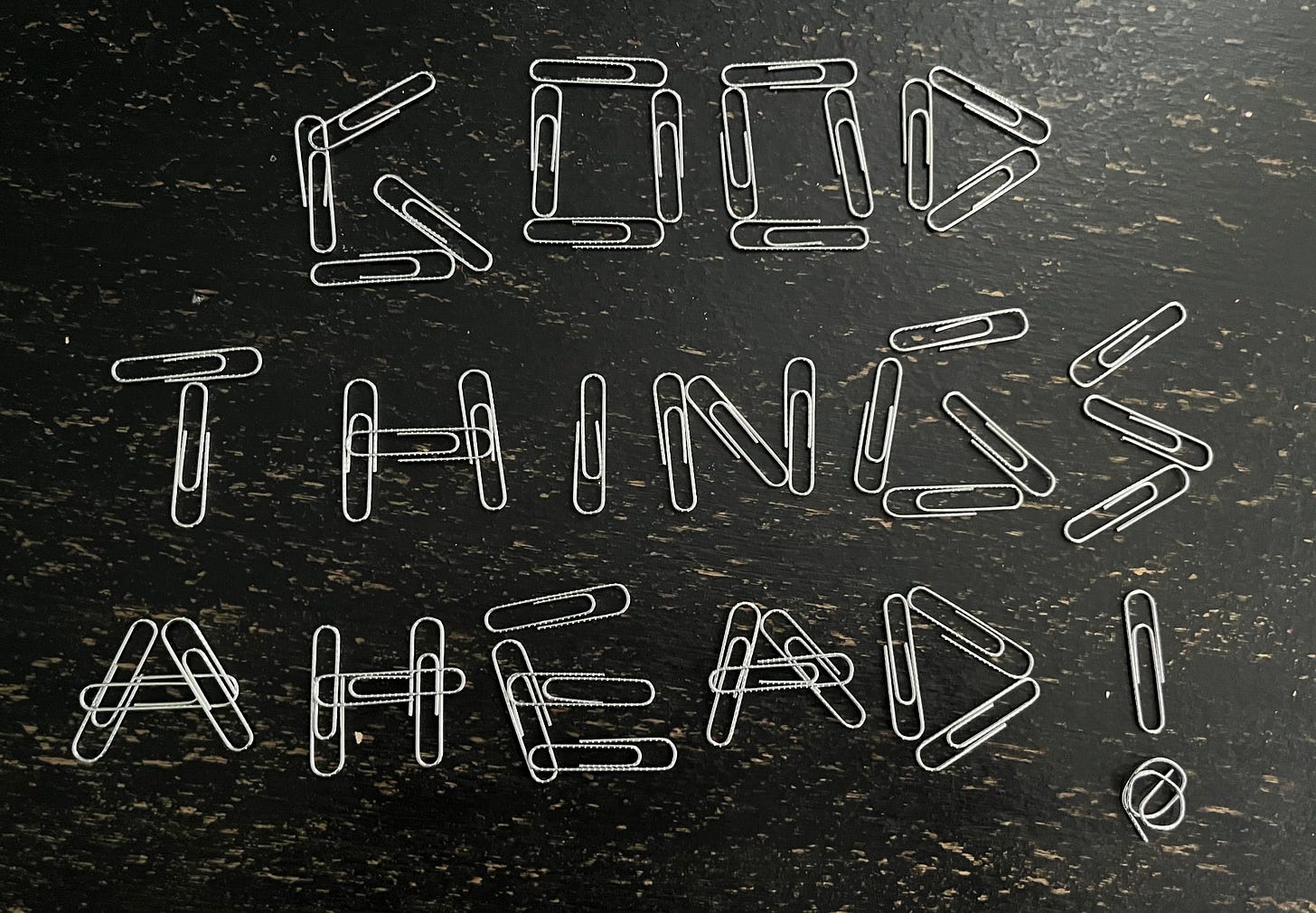

About a year ago, I began saying, ‘Good things ahead,’ at the end of conversations, emails, and texts. It started with professional correspondence and quickly crept into my personal life.

Whenever I fall back into depression, the darker parts of me argue that ‘Good things ahead’ is not universally true.

Surely there aren’t always good things ahead for all of us, the darkness says. So you sound moronic when you throw around that new catchphrase. Like a used-car salesman. A charlatan.

My analyst calls these darker voices “the rats in my brain.” He has also used the word sophistry. The darker parts of my psyche love sophistry. Their arguments are not designed to make my life better.

Maybe it all depends on how we define good things.

By the end of his life, Pop Pop’s singing days were long gone. But he had a devoted wife and a family who loved him. There were fresh vegetables from my grandmother’s garden and home-cooked meals and cards to play and sunsets and frozen strawberries and peanuts on vanilla ice cream and his favorite magazine, Reminisce, and harmlessly flirting with the grizzled breakfast waitresses at the local diner and playing pool with his buddies and Phillies games to watch and great-grandchildren to meet and so many other things that he loved.

The part of me that wants to keep breathing, the part that writes novels and screenplays and is excited to participate in this life, that Matthew Quick is aspirational. That Matthew Quick believes there are good things ahead, for me and for others. The good things might be small, but they are worth living for.

To quote one of my all-time favorite films:

“Get busy living. Or get busy dying.”

I think that’s the choice we all make every single day. And it’s a choice our characters need to make as well.

So I’m going to keep saying, “Good things ahead!” To myself and anyone else who needs to hear it.

That’s what you’re going to get from this Substack account.

G.T.A.