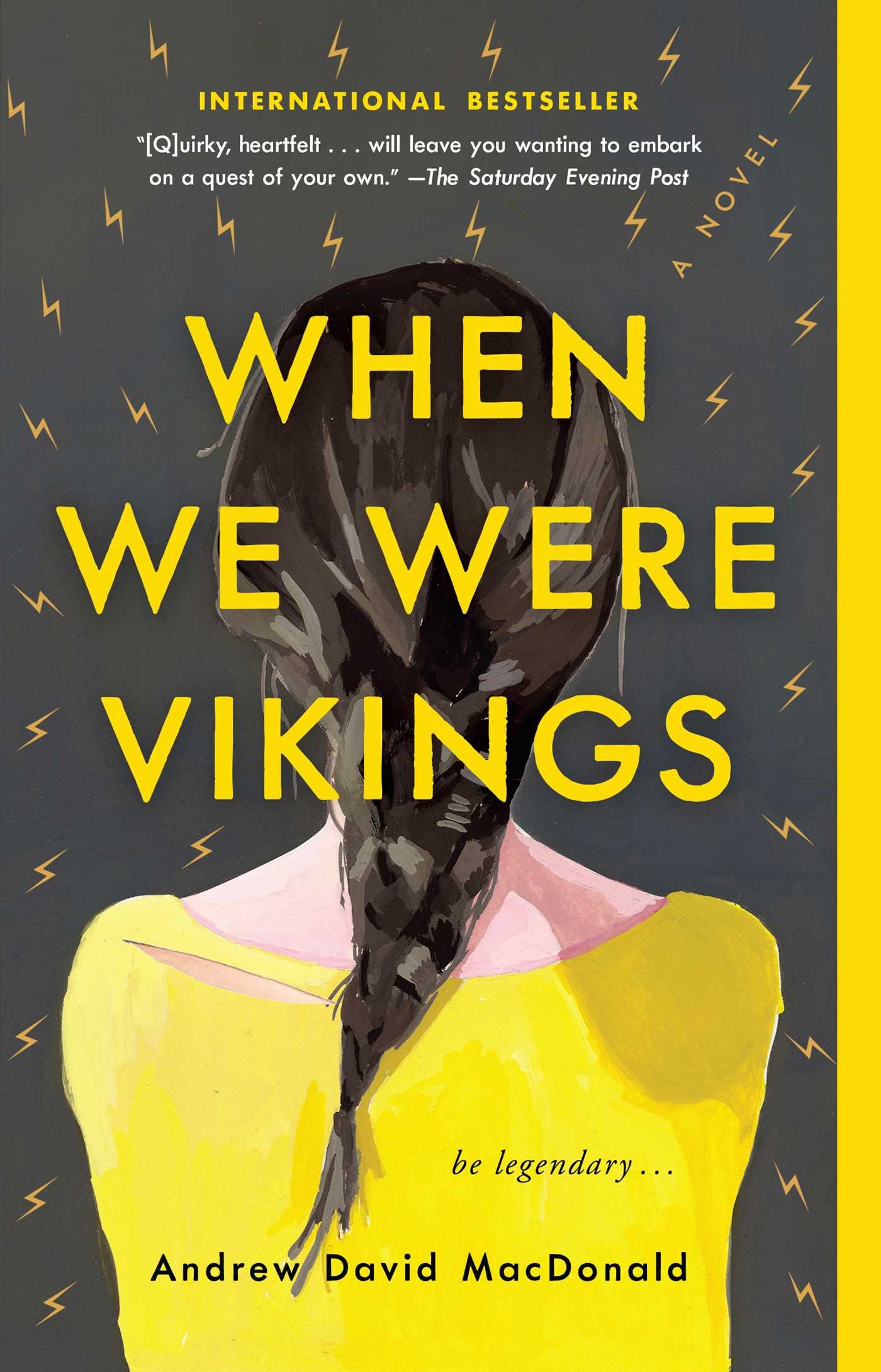

Andrew and I wrote the below interview via email in the fall of 2023, shortly after I finished reading his moving, life-affirming debut novel, When We Were Vikings, which was published by Scout Press / Simon & Schuster on January 28, 2020.

Matthew Quick: Welcome, Andrew. Or should I say, welcome back. You’ve many times contributed to the TWBM comment section under the initials A.D.

Andrew David MacDonald: Thanks for having me, Matthew! A pleasure to be here.

MQ: Internet research suggests that your debut got a lot of love and attention back in 2020. So I realize I’m supremely late to the party, as I just finished reading When We Were Vikings here in September 2023. What I lack in punctuality, I think I can make up in enthusiasm, because I kept reading this book late into the night, obliterating my sleep hygiene. Your winning first-person voice and heroic tale destroyed me in the best of ways. I cheered for Zelda as she tried to make sense of the modern world, using an obsession with vikings as an imaginative and grounding defense against the unstable realities of her life. And I sympathized with her older brother, the more off-screen Gert, as he tried to find a way to take care of his sister when he could barely take care of himself. It’s a novel about the great power of love to guide us out of trauma and family dysfunction. At times, it’s laugh-out-loud funny, but mostly I found it moving. I also found WWWV medicinal, in so much as I read it when I was feeling down and it reminded me that we can be heroic in everyday ways that make our lives richer and worth living. Thank you for that.

ADM: That’s very kind of you to say, and humbling, since I found the same medicinal quality when I first read The Silver Linings Playbook. When I started writing Vikings, the trend in fiction had skewed to the dark—novels about toxic friendships were popular, novels featuring deceptive relationships, sociopathic narrators, and what you might call a misanthropic view of humanity. It was the year (or three) of Gone Girl and suspense novels, a genre of writing I love to read myself. And in fact, the first draft of Vikings was quite dark; I won’t spoil the book, but that draft involved a significant character dying.

As I went through editing the drafts, though, I realized how exhausted I was by unrelenting bleakness. The novel started evolving into a story that celebrates the mess of existence, finding joy and love in a world that also deals out tremendous cruelty.

In a way I was lucky, because other writers and books around that time seemed to be riding the same wavelength. Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine came out just as I was completing my book, and there seemed to be a shift in the consciousness of readers, who gravitated towards stories where ordinary people struggle mightily and bravely in a sometimes dehumanizing world and, in the end, discover their own innate heroism.

Your work, incidentally, captures just that spirit. So again, it’s exciting to be chatting!

MQ: I’ve written some about the conscious vs subconscious reasons we novelists choose subjects. What was your conscious reason for writing When We Were Vikings? And looking back now with the book completed, what would you say you learned through the writing of this novel? Was there something previously unconscious that emerged? Maybe even snuck into the writing? Were you surprised by anything during the writing process? Have you been surprised as you revisit the story?

ADM: Stories often start as one thing and end up another, and it can be challenging to tease out where they come from. In the case of Vikings, I have a pretty good idea of the disparate parts that coalesced to make it.

It started with a short story I wrote, over a decade ago now. (Sheesh! Time flies!) It was about a brother in a low-income neighborhood who has to take care of his twin sister. As a result of his umbilical cord wrapping around her neck in utero, our hero feels guilty and responsible for her care. The story revolves around his discomfort around her having a sex life, and it was from his perspective, not hers.

It was the best thing I’d written to date. The story was anthologized in an anthology of Canada’s best stories and a few agents got in touch, saying they liked it.

I forgot it existed for a few years.

Over that time, I found myself turning to the characters, wondering how they were doing. At the same time, I realized that the anger and frustration my narrator felt over having to care for his sister mirrored some of the feelings I had about my mother, who during my teenage years had been in and out of psychiatric facilities for an often-debilitating mental illness. I saw that my subconscious was playing a game of substitution, and I started writing snippets, scenes, and dialogue from the perspective of the character of the sister.

Doing that helped me understand and heal a lot of the anger that I’d felt as a teenager, and to repair relationships with family members who I’d long since written off.

Anyway, those bits and bobs from Zelda’s perspective started coalescing. At the time I was writing a short script for a friend, who needed to film something for a film production course, and it was about a little boy who had a gigantic imaginary friend—a Viking. The meeting of these two separate threads braided together and helped me find Zelda’s voice.

MQ: Did you make any interesting and/or important mistakes while writing When We Were Vikings? If so, how did you cope? And what did you learn?

ADM: Yes. Many, many, many mistakes. I mentioned the book was much darker in its early incarnations, and it took a long time to find the right tone—the balance between the light and dark, and how to the find humor without belittling Zelda.

More significantly, there’s a sex scene in the book that I rewrote at least a dozen times. Spoiler: I’m terrible at writing sex scenes, and because of who the scene involves, it was the most frightening thing I ever attempted as a writer, because the stakes were incredibly high.

It’s a scene that a critic actually spent a great deal of time discussing in her review of Vikings. I don’t read reviews, really, but because this one appeared in a pretty big venue, perhaps the biggest, my agent forwarded it to me.

The reviewer had a lot to say about Zelda’s sexuality, and it made me wonder what kind of a novel would Vikings have been if I hadn’t included the sex scene that had scared me so much.

I remember thinking—as I was writing draft gazillion of that scene—whether I should just scrap it and not bother taking the risk of getting it horribly wrong and offending everyone. At that time I had no agent, no editor, nobody to say whether I was ruining my book by attempting something so risky.

But then I thought about my first writing professor and mentor, Larry Garber, who once said to the class that the things that make you the most uncomfortable and seem the most risky are exactly the kinds of things that make or break a book.

I firmly believe that to be true.

MQ: I’ve written about my own struggles with alcohol. Your heroine, Zelda, was born on the fetal alcohol syndrome spectrum. What led to your writing about this? Did spending time in Zelda’s head affect your relationship with alcohol? What’s you relationship with booze like these days?

ADM: I’m from Alberta, a province in Canada that has high rates of alcoholism and, as a consequence, people on the fetal alcohol spectrum. My best friend’s sister was on the spectrum, for example. Speaking of my relationship to alcohol, it started early—too early.

Several members of my family struggled, and still struggle, with alcoholism, drug use, and violence. I started drinking at twelve, largely because I was the youngest in a lower income family where there wasn’t much else to do.

Curiously, my father never drank or did drugs, and my mother never drank, since she couldn’t drink while on her anti-psychotic medication. But it felt like everyone else did, including a lot of my friends in the neighborhood and at school. I remember a girlfriend in high school telling me that I had a drinking problem, too.

It took awhile for me to recognize that for myself, and it was during writing the novel that I stopped drinking altogether. Boy, was that an experience.

I learned that I didn’t drink because I was genetically predisposed; I drank because I didn’t have the coping mechanisms to deal with trauma and pain. It felt like everyone else had developed the skills of emotional regulation during their teenage years, and that I had somehow missed the boat and was trying to stuff decades of maturation into months.

These days I rarely drink, if ever. I’ve watched people I care about, people with so much potential, abuse substances and die, get arrested, and become homeless.

MQ: WWWV’s publisher-made book trailer is available to view on Youtube. It’s a fun ad that seems to suggest a lighthearted story about vikings. And yet, the viking-obsessed Zelda’s heroism actually takes her into quite scary battles involving weapons. I’d say your novel is ultimately an intimate, rich character study of a modern young woman fighting for her autonomy. I happily experienced WWWV as much more serious than the trailer suggests. How do you pitch the novel these days?

ADM: My original pitch was “The Wire meets The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” a novel I still haven’t read.

The book’s post-publication life has been a strange thing—it occupies a kind of liminal middle ground between lighthearted book club and something more serious and darker. You can see this tug of war visually represented in the cover designs. Not to get too inside baseball, but it was challenging to figure out where to place the book, in terms of marketing, and the cover you included in this post probably indicates where the book ended up.

Which is to say: it took a design that was originally more literary and adjusted it to make it more book club friendly.

It’s kind of grotesque for me to think in those terms, but looking back now as a writer who now has readers—I still have trouble believing it; I’m grateful and it’s beyond my wildest dreams to have published this book—I can clearly see that it took a long time for me to discover who I was as a writer, and what books I’m meant to be writing.

MQ: Even though he makes some terrible choices, I related to Gert’s—dare we say masculine—need to be the provider and his genuine love for his younger sister. Zelda seems to need things that Gert doesn’t have and while strong women characters do step up to fill in the gaps, this book is primarily about an ill-fated brother-sister dyad that is forged by parental neglect and abuse. What led you to write about this?

ADM: I mentioned above that the story that spawned the novel was originally from the perspective of the character who would eventually become Gert. Getting a bit more granular, the original story was about the frustration of someone with a lot of potential who, because of his upbringing and some bad luck, never fulfills that potential because of family obligations.

In the story and novel, it’s a brother and sister dyad, as you elegantly put it.

Growing up for me, it was a triad of my mother, my brother, and me.

Gert’s personality, his quirks, and some of his bad choices are an amalgamation of family members of mine, and friends, who made similar choices.

In a somewhat vague, writer-says-cryptic-thing way, all of the characters have parts of me, too, and it was only by sheer good fortune and the steadying hand of some people who took the time to mentor me that I didn’t end up like Gert myself.

MQ: I really felt for Gert. His dreadful decisions are somewhat prompted by his having been forced at a too-young age to save and take care of Zelda. Gert seems to represent the modern trend of young men dropping out—of school, life, relationships. Zelda takes full advantage of therapy and social services and the library, while Gert is more reluctant to use those resources.

The thing I love about unreliable first-person narratives is that we readers have to psychologically puzzle out the other characters as we look through the distorted lens of the narrator’s current—and usually changing—worldview. I find that fascinating. And—other than Zelda, obviously—Gert was who I thought about most while reading. Maybe because I once was a deeply wounded hard-drinking young man who was avoiding the difficult inner work of analysis (or therapy). Like Gert, I had a remarkably hard time loving myself enough to embark on the quest to improve my own lot.

These days, we hear much about toxic masculinity, but less about why men become toxic.

I think Zelda’s great love for her brother really humanizes him, even as he fails to be what she needs. The last chapter was truly masterful. This male reader was definitely crying.

I think the story truly is Zelda’s and you chose your narrator well. All that said, do you think you could have written a version of this story from Gert’s point of view? How do you feel about Gert? Do you struggle at all with your own sense of masculinity?

ADM: This is a complicated question to answer.

On a purely nuts and bolts perspective, yes—a novel could have been written from Gert’s perspective. The original story was, for example. I’ve only recently read Boy Swallows Universe, but I somewhat see that fantastic novel as the sort of thing that Vikings might have been. (And by that I mean that kind of story. Boy Swallows Universe is so magnificent I have trouble comparing anything I’ve done to it).

But there’s more to the question than that—and as I’m mentally unpacking the ‘moreness,’ I’m feeling an acute discomfort and fear of ‘getting it wrong.’

I’ll say this: you cannot treat disaffection and alienation and loneliness with shame. Gert’s terrible choices come about because of those things; he was drawn to someone like Toucan because Toucan, however perverse and warped, represents the opportunity for belonging that I suspect many young men and boys are looking for.

It’s no secret that ‘masculinity’ as a concept has taken a beating in the cultural discourse in the last decade, and in a lot of ways a course correction was and is completely necessary.

At the same time, I’ve watched a lot of good men and boys struggle mightily, with few or no outlets to find belonging and love. As a boy and young man, I found love and friendship in sports and by having good male mentors, but I did so in a largely offline world. I’m at the age where a lot of my dear friends are raising sons, and many of them are confused and unsure about how to raise them in a culture that seems unsure of how to treat its boys and young men.

You might have picked up on the care with which I’m talking about masculinity; does it feel like a minefield to you like it does for me?

MQ: It does indeed, which is part of the problem, right?

As I mentioned before, Zelda’s viking obsession seems to function as a psychological defense against her precarious reality. She does get into some serious trouble on her quest to become “legendary,” but the viking enthusiasm mostly provides Zelda with a much needed personal life philosophy, filling the void left by absentee and abusive parental figures.

Sometimes I’ve wondered if I’ve used the fantasy of ‘being a writer’ as a psychological defense. Especially at the beginning, before I was published. Instead of viking lore, I studied and awkwardly tried to emulate the lives of Vonnegut, Hemingway, Murakami, Gao Xingjian, and many others. Have you used fantasy in your life to get through tough times? If so, how?

ADM: Part of the way I’ve always coped with a chaotic upbringing was through monomania. I wrestled, played sports, and obsessed about athletics as a teenager. Doing so got me out of the house and gave me a framework by which I could value myself.

When my athletic career ended, I was overwhelmed—the practices I used to measure my worth as a human being, in a life that didn’t seem to value me at all, were gone.

Without athletics, what was I?

I failed most subjects in high school, but I was a closet reader. Both my mother and my brother had a streak of genius to them, and they instilled in me a love of reading that, looking back, seems completely bizarre, given the kind of lifestyle we otherwise had as a family.

When I graduated high school, I relocated to another high school, across the country, for the chance to play another year of sports while living with my aunt. This choice, driven by an almost pathological need to continue my identity as an athlete, ended up being the best decision of my life.

I did play that final year of sports, but I also met someone who read a lot, wrote a lot, and who loved a book called The World According to Garp. I had a big crush on her, despite our Breakfast-Club-mismatch of high school archetypes, and decided to read Garp. That was it. The novel changed everything.

It’s about a wrestler who woos a bookish girl through writing; I was a former wrestler who was wooing a bookish girl through reading a book about a wrestler who woos a bookish girl through writing. It was startlingly meta, but more than that, the tone of the book, the characters, the mix of light and dark and lunacy and sorrow, touched something very deep inside of me.

Thus: I started writing.

To circle back to the initial question, one part of maturing and becoming this thing called ‘adult’ is realizing who you are and balancing the urge to improve yourself with the need to accept your core being.

I’ve learned that my monomania isn’t going away, and that being a writer is who I am. That means I won’t always find balance in my life. Often at social events I’ll be thinking of my writing project instead of being more mentally and spiritually present. I’m often devastated when something I write doesn’t pan out.

When my writing isn’t going well, I’ll often end up feeling the same valuelessness that overwhelmed me when I was no longer an athlete.

The good thing about writing, the twin to its curse, is that you never reach the finish line. So it’s always there.

MQ: Zelda attempts to live by a code which is mostly informed by Dr. Joseph Kepple’s Guide to the Vikings. She likes rules. What are your top three rules for living the writing life?

ADM: I’ll offer two practical tips and something more philosophical. Read – a lot, and outside of your comfort zone. In the last month, I’ve read a romance novel, a horror novel, and a classic novel with next to no dialogue.

Find what feels dangerous or uncomfortable in your writing and explore that. Which is to say: take risks. Big ones. You have to create a space for yourself where you can make mistakes, even ugly ones.

Finally, I have a thesis that to finish a novel, you’ll inevitably have to overcome whatever wounds you have off the page. Writing is a fractal of your life; the more emotionally and spiritually sound and healthy you are on a random Tuesday, the better equipped you’ll be to write the book you’re meant to write.

MQ: Sade tells us it’s never as good as the first time. How has the writing life been since you’ve become an officially published novelist? What have you learned through the transformation? Did anything surprise you?

ADM: I love Sade. Nice reference. Let’s see. There’s the inevitable hedonic adaptation, of course. There’s the absolute joy I get when I receive emails from people who found meaning in my book. I’d be lying if I didn’t acknowledge that the financial rewards revolutionized my life and put enough space between me and my ever-present fear of ‘going back’ to the world I grew up in.

One surprise: I thought publishing and Hollywood was filled with conniving, money-grubbing bastards who treat authors and writers like second class citizens. This has so profoundly not been the case that I’m almost ashamed to have thought it.

One not-surprise: Happiness is an inside job, though I don’t like the word ‘happiness,’ which feels like a transitory state that needs to be balanced out with heartbreak and struggle to have any meaning whatsoever. Which is to say: I thought publishing a book might fix everything about myself I didn’t like. I would never again have to feel inadequate or insecure again, because I did the thing and achieved my lifelong dream. I had arrived.

You never fully arrive, though. And not to get too woo woo, but it’s like Alan Watts says, and I paraphrase: one doesn’t dance in a rush to get to the end of the song. The dance is the point, not the end.

MQ: I’m looking forward to reading your next book, which is in the works, right? And, I’m rooting hard for the movie adaptation of When We Were Vikings. I think it would make a fantastic film. Can you talk briefly about those?

ADM: You know, I have no idea what I’m even allowed to say. I’m just a kid from the prairies of Canada, so the business of Hollywood feels like it lives on another planet.

Which I suppose it does.

But what the hell—if I get an email from someone sassing me, I guess I’ll have to be more coy.

Vikings is marching through the system as we speak. It’s been optioned by an Oscar-winning director, has a team of great writers, and producers who have produced movies that make my knees ache.

I still can’t really believe I get to have meetings with these people.

They are a fantastic group of humans, and I feel blessed to be able to work with them.

Nothing is set in stone, of course. But every once in a while, when the void becomes and the universe seems bleak and uncaring like something out of H.P. Lovecraft, I think: holy sh!t, these people actually liked my book and believe in it enough to write a script and buy the rights to it and put in hours and hours of work to make it into a movie.

MQ: Tell us fellow writers something inspiring. Give us some fuel to keep punching keyboards and scribbling in notebooks. Lift us up before you go.

ADM: Yes please! I’m so sick of pessimistic screeds against books and publishing and the writing profession and all the awful stuff we’re bombarded with, day after day. Just like no fish can survive swimming in a pond saturated with toxic waste, no creative life can exist if the person living it mainlines nihilism.

There’s always plenty to be anxious about, but a wise friend loaned me a book about curiosity that had a great metaphor, which I will do my best to reproduce.

Imagine you have a radio, and the anxiety and fear knob is turned way up, so loud that you can barely think, let alone write, or create, or love, or feel like you’re living a meaningful life. No matter how much you fiddle with that knob, the sound keeps going. A lot of the time, our lives are spent on that knob, trying to turn down the volume of anxiety and fear—so much so that we don’t even notice a second knob.

That knob is ‘curiosity.’ And you absolutely can turn that one up. In one of the psyche’s sadistic paradoxes, it can be completely unfruitful to try to ‘fix’ a problem like fear or anxiety. Instead, sometimes you can revolutionize your creative practice and life by focusing on curiosity and exploration—seeing scary things like facing the blank page as a place to be curious and explore.

It’s metaphor I’ve been thinking a lot about, as I turn (gulp) forty and think about the second half of my life.

MQ: Thanks so much, Andrew, for dropping by There Will Be Mistakes. I’ve really enjoyed reading your work and getting to know you a little better. Best wishes on everything.

ADM: Lovely to be here, and thank you for the chance to chat.

Buy When We Were Vikings. (Seriously. Buy it right now. You will love it.)

Learn more about Andrew David MacDonald.